Nudes fascinate and outrage; excite and inspire. Depicting unclothed bodies offers virtually infinite possibilities for rendering our perception of ourselves and expressing our ideals, fears and dreams. Nudes form a specific artistic genre that constantly reinvents itself to communicate social, political, and aesthetic matters.

Nude, the [njuːd] (engl = Akt): Glossar According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a nude is a picture or other piece of art showing a person who is not wearing any clothes.

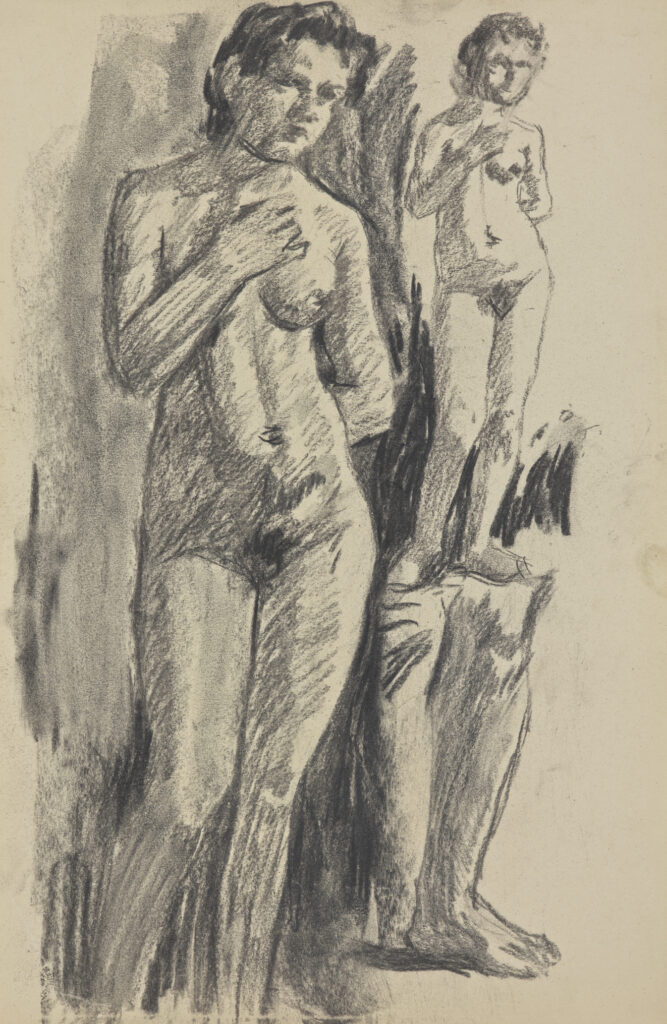

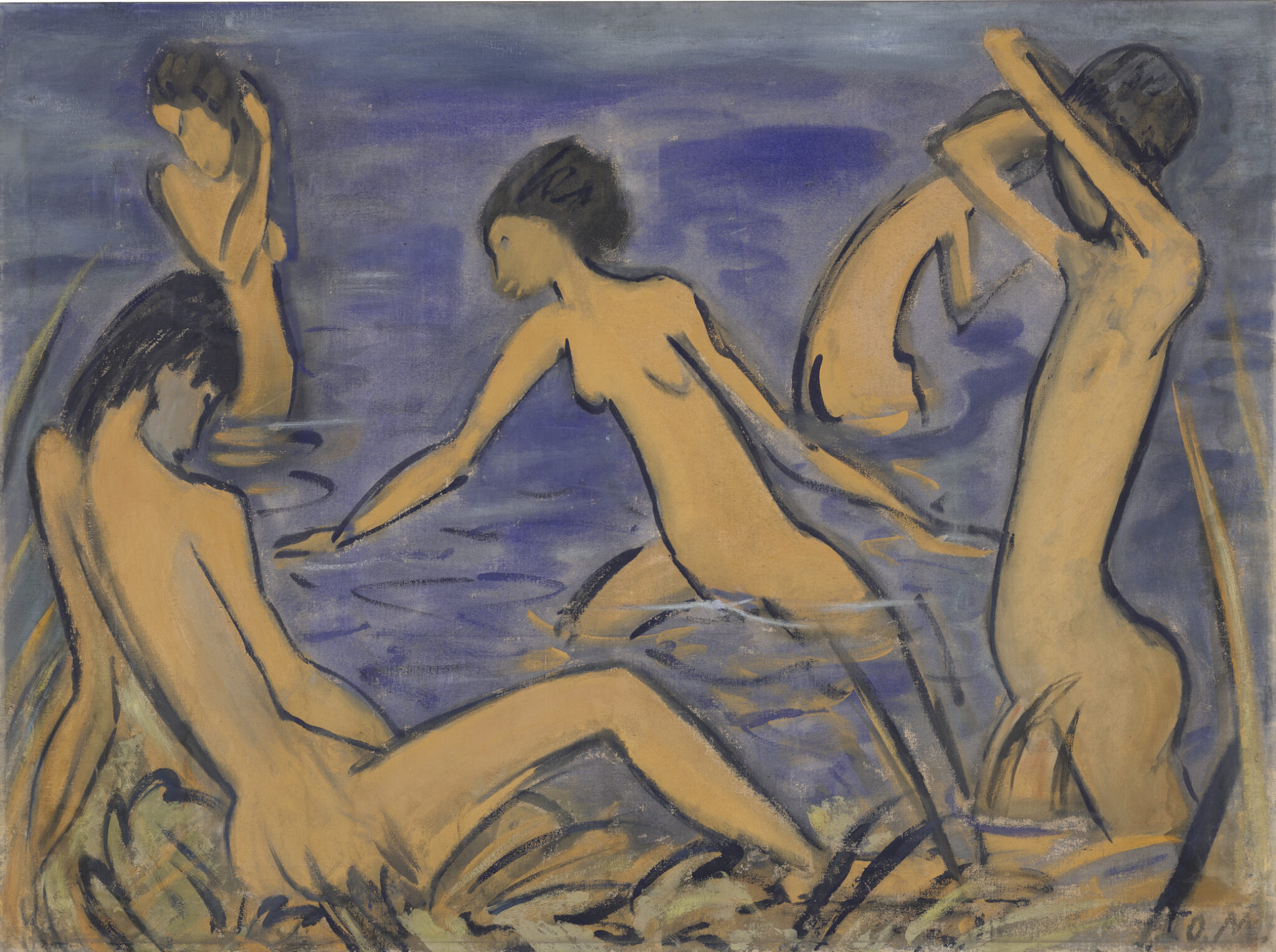

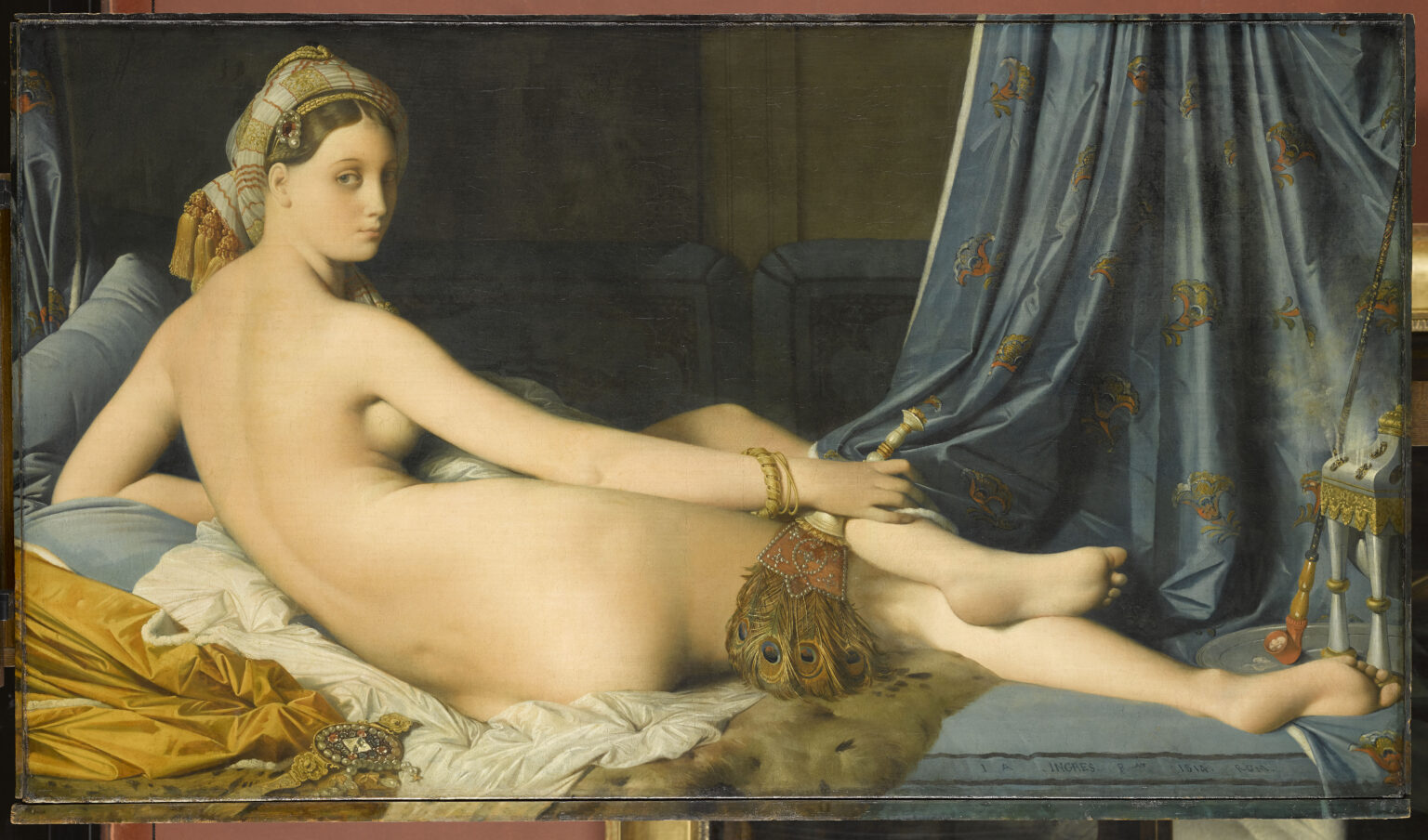

Until the 20th century, artists who intended to depict unclothed human bodies without infringing on social and moral rules had to embed their nudes in biblical, classical, or literary contexts. Such works assign gender-specific roles to the figures: men have active and heroic attitudes, while women seem passive and vulnerable.

Male Gaze, the [meɪl geɪz]: Definition of male gaze in the Cambridge Dictionary: “the fact of showing or watching events or looking at women from a man’s point of view”, and to sexualise the female body.

The Knight Errant, a work by Sir John Everett Millais that figures a naked woman modestly looking away as an armoured knight cuts her bonds, caused a sensation when it was presented to the public. Although the character of the knight-errant is common in medieval literature and the woman on the painting is rendered in a passive and submissive attitude that meets the standards of the 19th-century art, critics felt that she was too life-like and assumed that she had loose morals.

Interestingly, recent x-ray photographs of the painting show that in the original version of the work, the woman had a clearly more active attitude, turning towards the knight and establishing direct eye contact with him. However, as the painting did not sell, Millais retouched his work and adapted it to the mores of his time and to the male gaze.

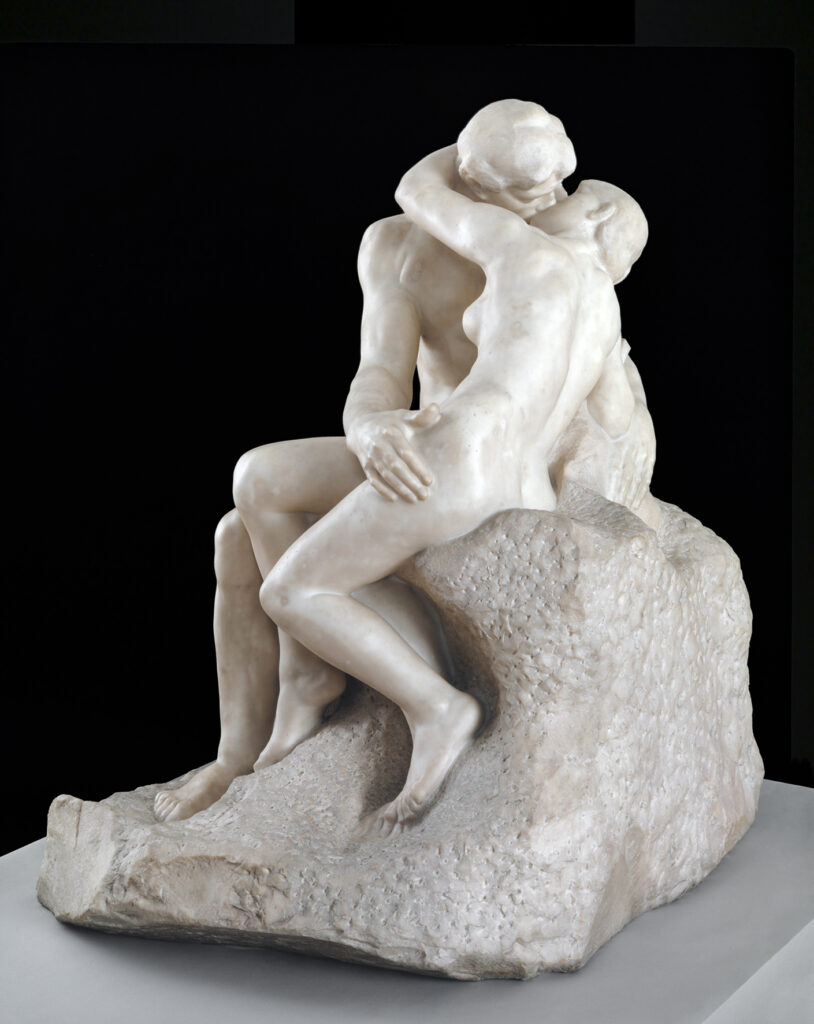

The most important thing is to be moved, to love, to hope, to tremble and to live. To be a human rather than just an artist.

(Auguste Rodin)

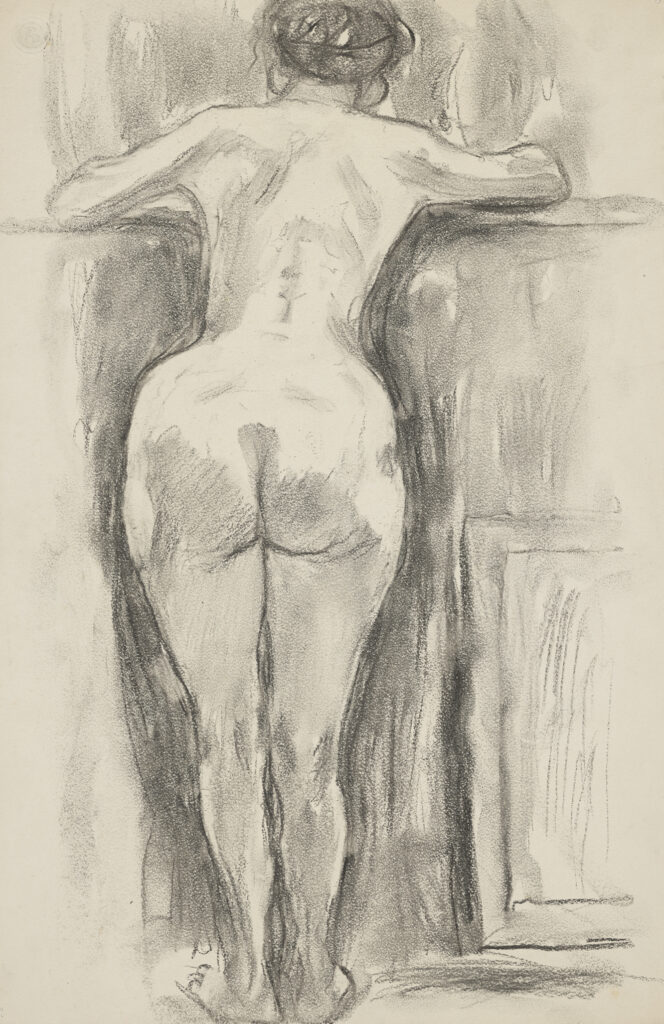

In artworks depicting women bathing or washing themselves, the figures seem unaware that somebody is watching at them; the viewpoint is that of a voyeur observing a scene through a keyhole.

Towards the end of his career, Edgar Degas created several such nudes, in particular the finely executed pastel presented here. It was part of a series shown at an Impressionism exhibition held in Paris in 1886. Some art critics praised Degas for depicting credible, modern women, while others complained about the ugliness of the models and insinuated that they were prostitutes. In this pastel, however, there is no reference to the woman’s social status. What is your opinion?

Voyeurismus, der [vo̯ajøˈʁɪsmʊs], (fr. voir = see): a person who takes sexual pleasure from secretly watching other people in sexual situations, or (more generally) a person who watches other people’s private lives.

I appeal to a Sense of Form. In some of the works I show in the first room, I completely abandon Naturalism and Tradition. I am searching for an Intenser expression. In other works in this room, where I use Naturalistic Form, I have stripped it of all irrelevant matter. […] My object is the construction of Pure Form.

(David Bomberg)

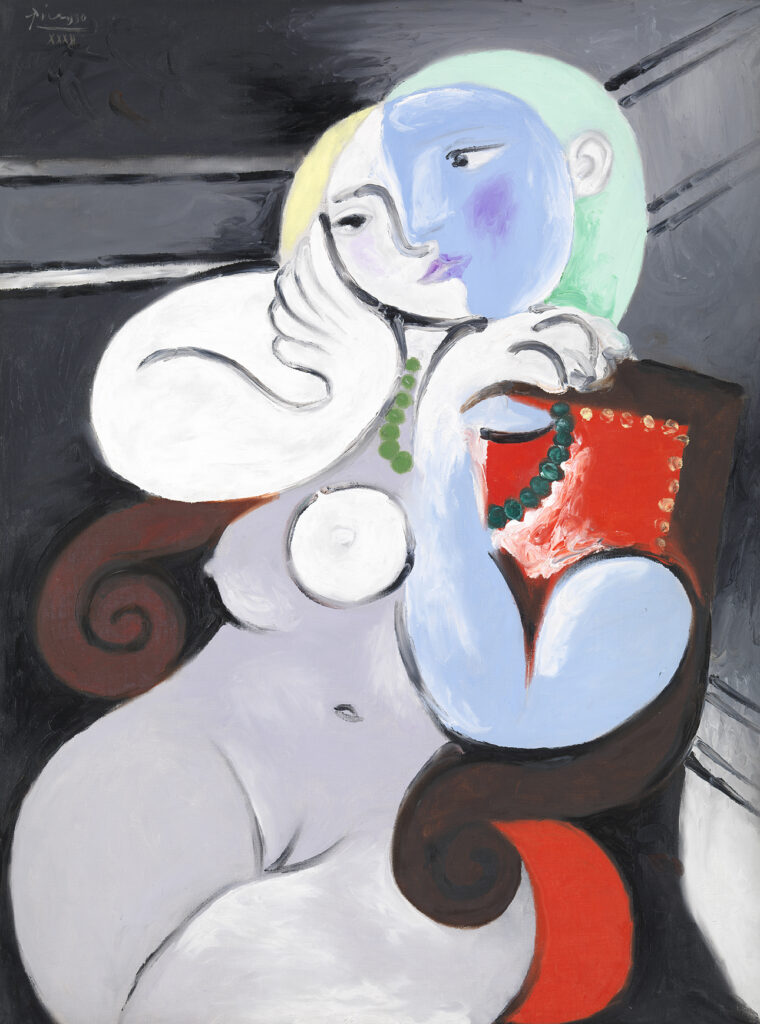

Avantgarde, die [avɑ̃ˈɡaʁdə]:ideas, styles, and methods that are very original or modern in comparison to the period in which they happen. This applies in particular to 20th-century art movements that promoted progressive and radical politics and criticised the dominant aesthetic norms.

Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) Die Ungewissheit des Dichters, 1913 The Uncertainty of the Poet, 1913 Tate. Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund (Eugene Cremetti Fund), the Carroll Donner Bequest, the Friends of the Tate Gallery and members of the public 1985 © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023 Foto: Tate

Surrealist artists used nudes to explore the various facets of a dream-like world. The unclothed bodies in their works seem strange and alien, which is in line with the definition of the term “surrealism”: superior or higher reality. The surrealist movement included not only painters, but also writers, photographers, and filmmakers.

1. The sculpture in the painting by De Chirico is a torso of the Greek goddess Aphrodite.

2. This ancient work contrasts with the passing train in the background, which refers to the present.

3. Shadows and a distorted perspective undermine the conventions of pictorial space and time.

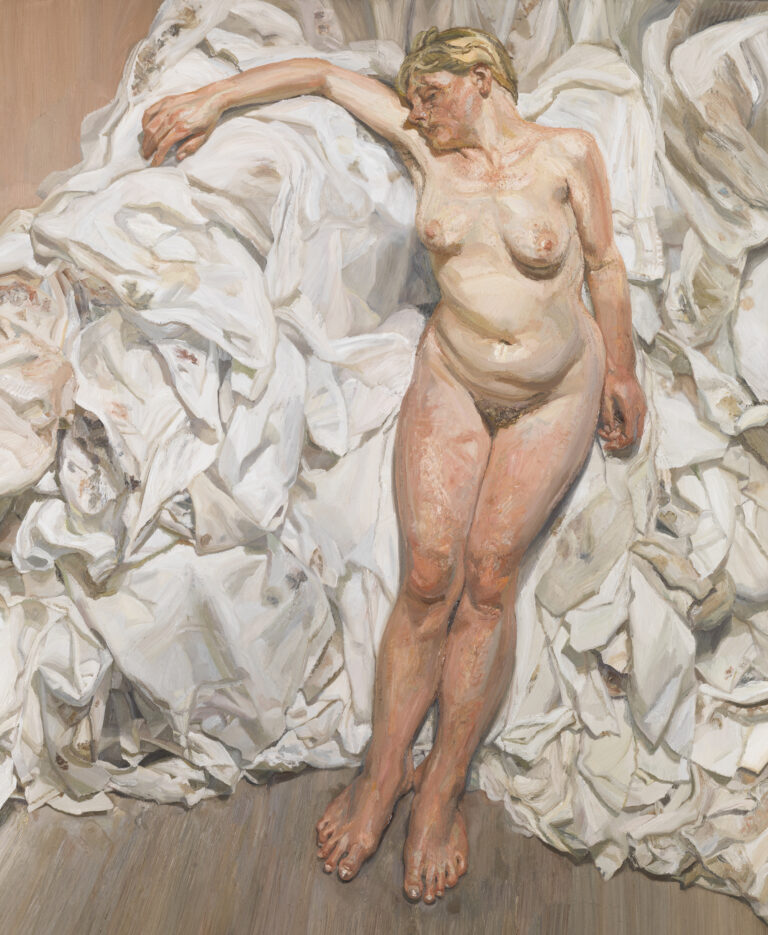

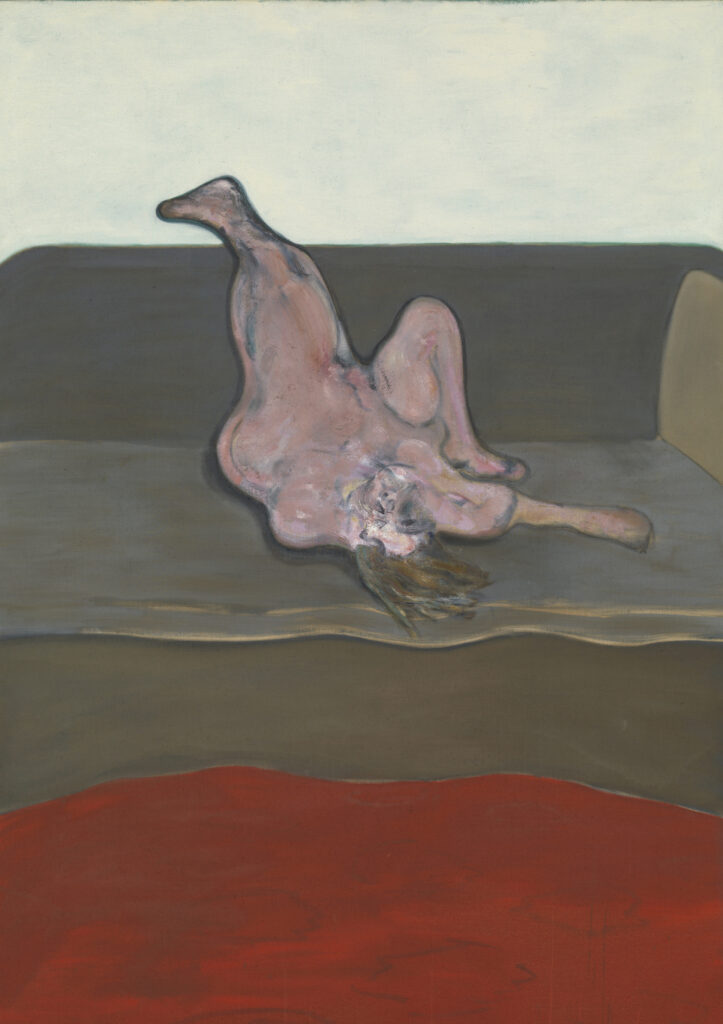

When I look at a body I know it gives me choices of what to put in a painting; what will suit me and what won’t. There is a distinction between fact and truth. Truth has an element of revelation about it. If something is true, it does more than strike one as merely being so.

(Lucian Freud)

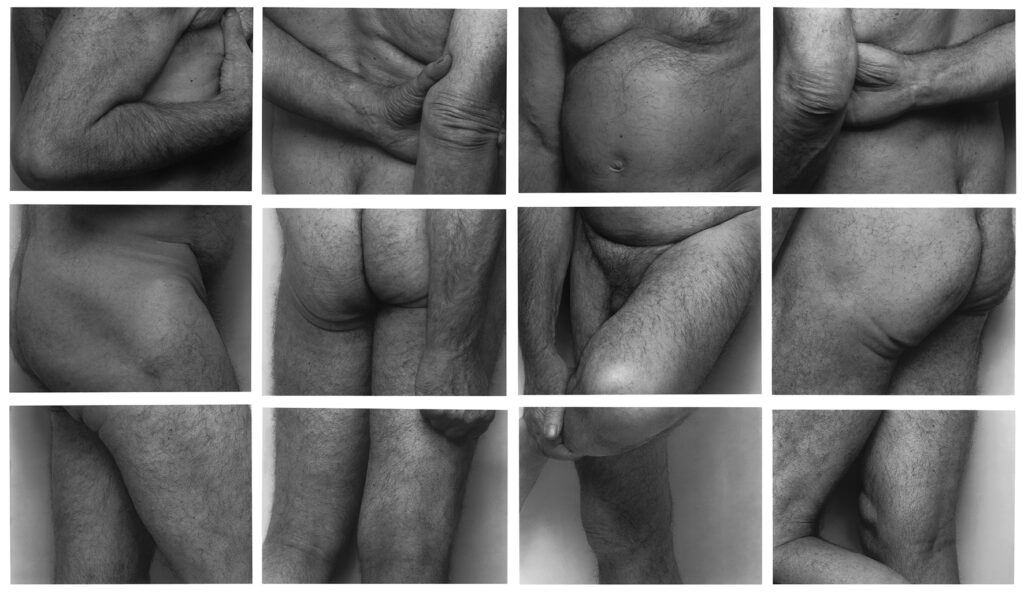

The carnal, physical nature of the human body, the materiality of its skin, muscles and tissues, is involved in many aspects of human life.

Beauty ideal, : the way people understand beauty of the face and body at a particular time in a particular culture.

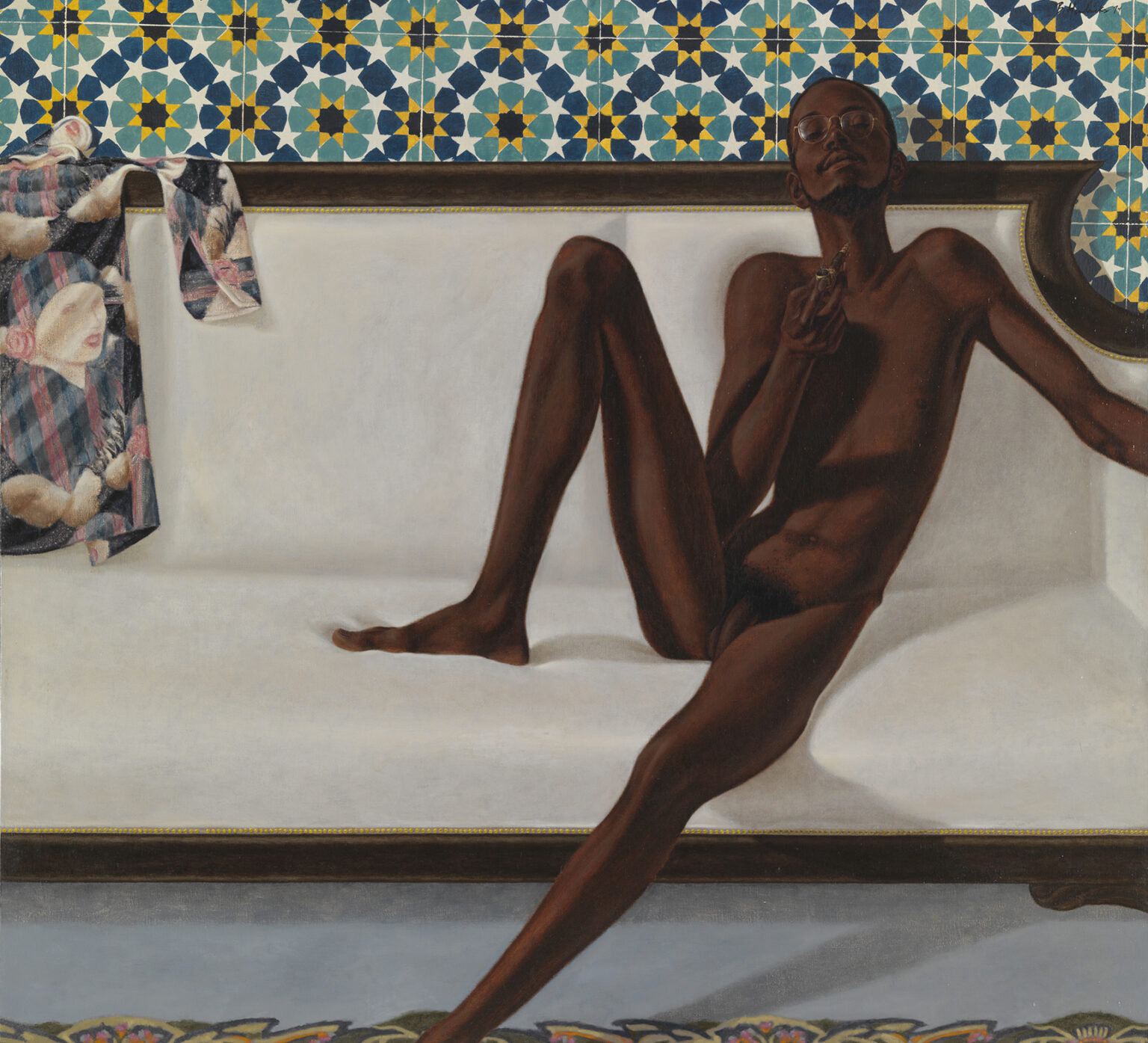

The model, George Jules Taylor, sits naked and relaxed on a sofa; his coolness provides his nudity with an inconspicuous touch; he gazes at us with his chin raised as he smokes. Is this attitude provocative or does it allow us to approach the young man without tension?

In the 1970s, Barkley L. Hendrick created several portraits of George Jules Taylor that express the dignity, pride and self-confidence of people of colour. Since that time, a growing number of exhibitions have been organised specifically to feature people from various non-white communities.

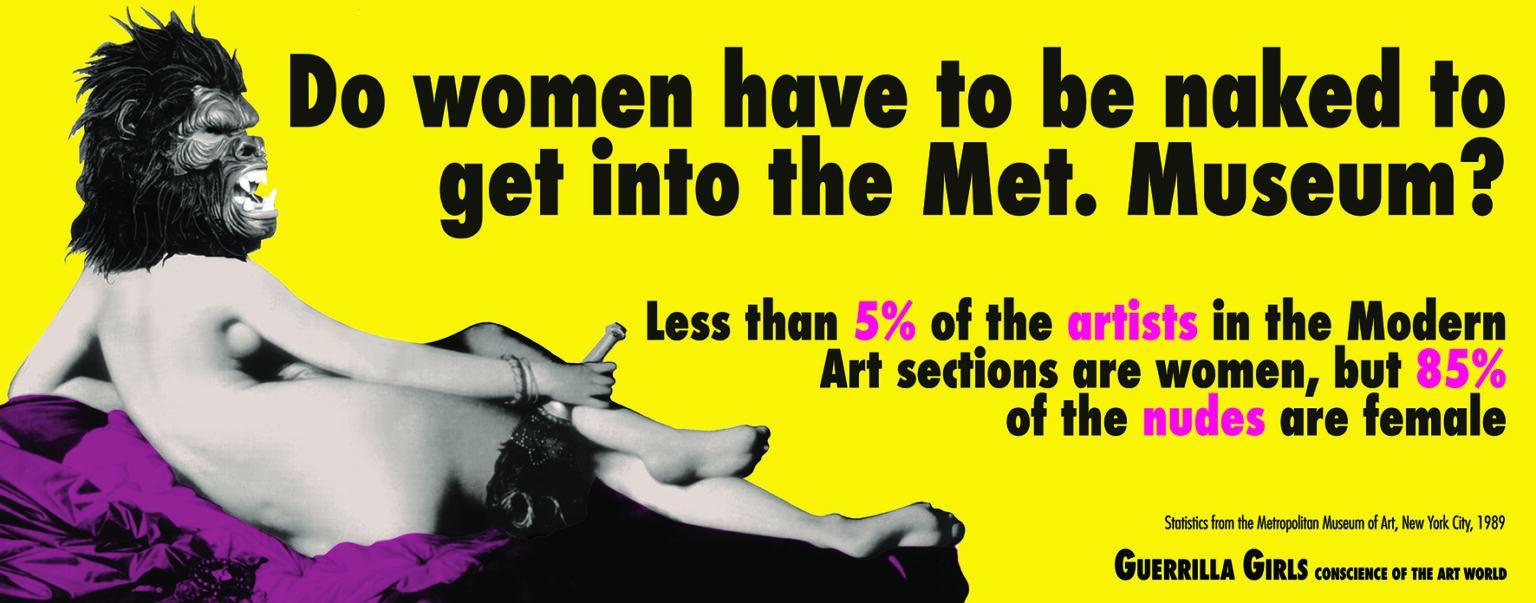

Art has a political dimension and is a mirror of its time. Over centuries, many artworks have showed naked women painted by men for men, but things started to change in the 1970s. The rise of feminism initiated a political debate about nudity that intended to challenge sexual and race stereotypes. Still today, roles are being renegotiated.

Empowerment , the [ɪmˈpaʊə.mənt]: the process of gaining freedom and power to do what you want or to control what happens to you.

Why have there been no great women artists?

(Linda Nochlin)

Alice Neel portrayed her colleague Kitty Pearson directly and unfiltered, without concealing the model’s lack of confidence and awaiting attitude. What message do her gaze and body language convey?

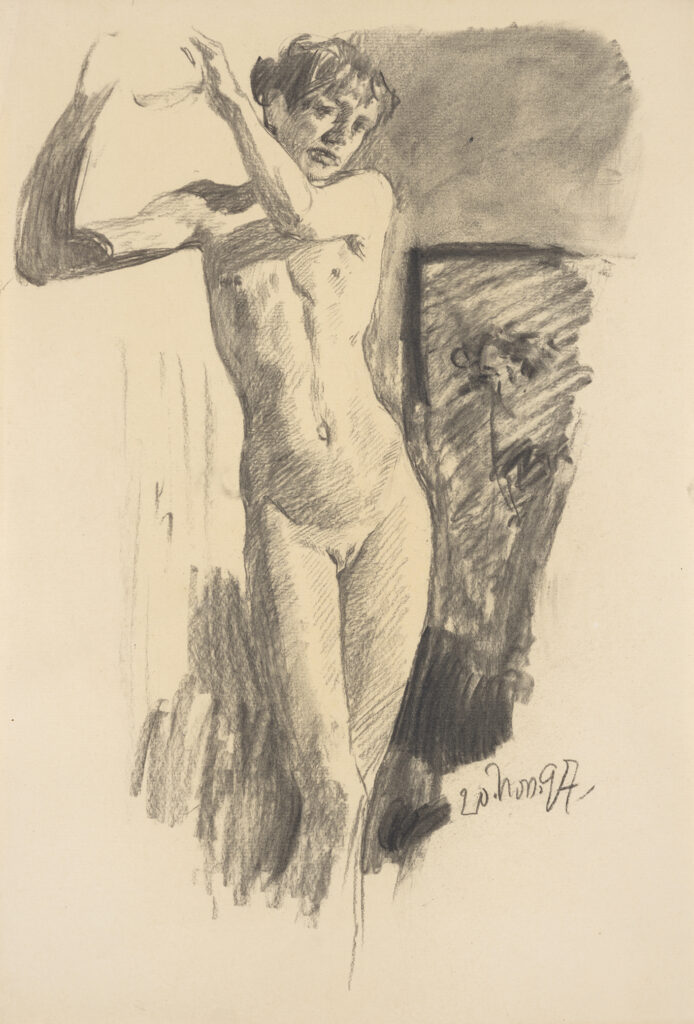

Female artists remained the exception until well into the 20th century. In 1971, this prompted Linda Nochlin to publish an article sarcastically entitled: Why have there been no great women artists? The answer in just a few words: over centuries, talent in art was judged by men who excluded women artists from museums and art history. One of Nolchin’s specific arguments fits the context of the present exhibition: history painting used to be considered the highest artistic genre and the most suitable for artists to evidence their talent. As women had no opportunities to paint nudes, compulsorily embedded in historical contexts over centuries, they were unable to demonstrate their genius.

Linda Nochlin is therefore considered a trailblazer in feminist art history. However, it took more than forty years for museums and scholars to begin reconsidering the question. Even the present exhibition shows more works by male than by female artists, especially from past centuries.

LGBTQI+ , [el.dʒiː.biːˈtiː kjuː aɪ plʌs]: abbreviation for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and more”.

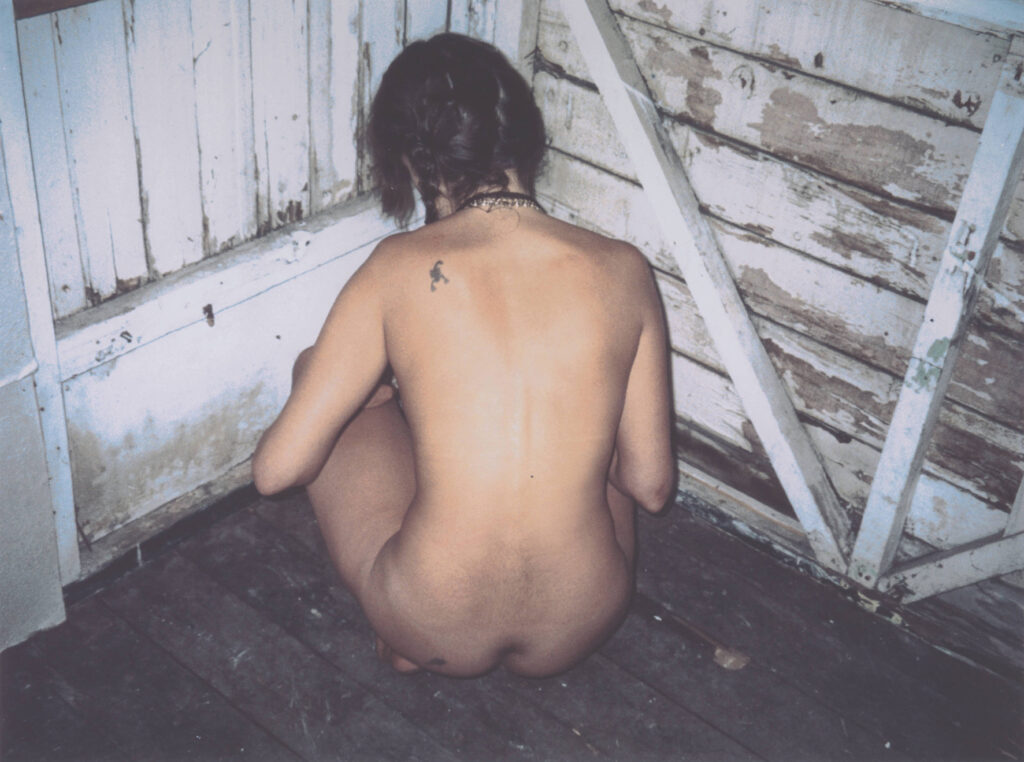

While ancient artists created nudes that embodied an idealising approach to beauty, the profane depiction of unclothed people was considered a sin in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, examples of sacred art depicting Adam and Eve without clothes, or Jesus Christ almost naked on the cross, intended to show how vulnerable humans can be. Contemporary artists still render our vulnerability, thus expressing a variety of fears that exist across society.

The camera looks down on a naked woman huddled in a corner of a ramshackle hut. The close-up centering heightens the creepy atmosphere. This self-portrait by Tracey Emin triggers protective instincts, as we wonder “What’s going on here?” The photograph’s title, The Last Thing I Said to You was Don’t Leave Me Here II, opens up several levels of interpretation.

Although artists usually express their own feelings and values in self-portraits, that of Emin presented here conveys the impression that it also reveals the public’s gaze. The artist explores her own biography, starting with her childhood. This may be uncomfortable for many people, but creating such artworks enables her to overcome traumas.

Nude as a statement

Artists have been creating nudes for thousands of years, albeit the media and techniques involved have changed over time. The relationship between artists and models also changed during the 20th century. Moreover, as their relationship is no longer determined by a one-sided, dominant gaze, artists are able to give a voice to a variety of people, thus creating a platform to talk about social and historical issues, including racism and discrimination.

Dealing with desire, truth, mortality and equality, the nude expresses identities and enables us to be ever more aware of social diversity.

Insider tip

Share your experience

#LWLMKK #ABOUTNUDES